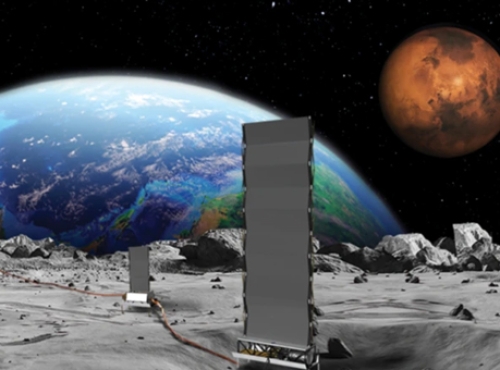

The U.S. space agency NASA has committed to expediting a plan to launch a nuclear reactor on the moon by 2030, according to U.S. media reports. It forms part of American efforts to establish a lasting human settlement on the lunar surface. Politico reports that NASA’s acting director referenced comparable programs in China and Russia, cautioning those countries “could potentially declare a keep‑out zone” on the moon.

Still, doubts persist about the feasibility of the proposed timeline in light of steep recent NASA budget reductions, and some scientists worry the initiative is driven by geopolitical considerations, BBC reports.

Countries including the U.S., China, Russia, India and Japan are accelerating lunar exploration and some are pursuing long-term human bases. US Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy, serving temporarily as NASA chief by presidential appointment, stated in a letter to NASA—according to the New York Times—that “To properly advance this critical technology to be able to support a future lunar economy, high power energy generation on Mars, and to strengthen our national security in space, it is imperative the agency move quickly.” He called for bids from private firms to develop a reactor capable of delivering a minimum of 100 kilowatts.

While modest—since a typical land-based wind turbine produces 2–3 megawatts—it reflects NASA’s strategy. The concept of a lunar nuclear power source is not new. In 2022, NASA awarded three contracts of $5 million each to companies for reactor design studies. In May this year, China and Russia unveiled plans for an automated lunar power station to be operational by 2035.

Many scientists agree that reliable continuous energy on the moon may depend on nuclear technology. A lunar day lasts four Earth weeks, consisting of two weeks of daylight followed by two weeks of darkness, rendering solar reliance highly unreliable. Dr. Sungwoo Lim, senior lecturer in space applications, exploration and instrumentation at the University of Surrey, asserts that “Building even a modest lunar habitat to accommodate a small crew would demand megawatt‑scale power generation. Solar arrays and batteries alone cannot reliably meet those demands.” He adds: “Nuclear energy is not just desirable, it is inevitable.”

Lionel Wilson, professor of earth and planetary sciences at Lancaster University, believes deploying reactors on the moon by 2030 is technically plausible “given the commitment of enough money,” and points out that small reactor blueprints already exist. He adds that the limiting factor is having sufficient Artemis launches to assemble lunar infrastructure in time.

Safety questions remain. Dr. Simeon Barber, a planetary science specialist at the Open University, notes that “Launching radioactive material through the Earth's atmosphere brings safety concerns. You have to have a special license to do that, but it is not insurmountable.”

Duffy’s directive surprised many, coming after a turbulent period at NASA following a 24% budget cut set for 2026, including significant reductions to science initiatives like the Mars Sample Return mission. Some scientists express concern that the announcement reflects a politically motivated return to nationalistic lunar competition. As Dr. Barber says: “It seems that we're going back into the old first space race days of competition, which, from a scientific perspective, is a little bit disappointing and concerning.” He adds: “Competition can create innovation, but if there's a narrower focus on national interest and on establishing ownership, then you can lose sight of the bigger picture which is exploring the solar system and beyond.”

Duffy’s remarks about China and Russia potentially declaring “keep‑out zones” refer to the Artemis Accords, an agreement signed by seven countries in 2020 to define cooperative principles for lunar surface operations. The Accords allow for “safety zones” to be established around facilities on the Moon. Dr. Barber explains: “If you build a nuclear reactor or or any kind of base on the moon, you can then start claiming that you have a safety zone around it, because you have equipment there.” He elaborates: “To some people, this is tantamount to, "we own this bit of the moon, we're going to operate here and and you can't come in".”

Barber also stresses the outstanding challenges before a human-use lunar reactor becomes viable. NASA’s Artemis 3 mission is planned to carry astronauts to the lunar surface in 2027, but has been beset by delays and funding uncertainty. “If you've got nuclear power for a base, but you've got no way of getting people and equipment there, then it's not much use,” he warns. “The plans don't appear very joined up at the moment.”